5 Git Concepts That Will Supercharge Your Workflow

For many developers, learning Git follows a familiar path. You master git add, git commit, and git push, and suddenly, you have a reliable system for saving your work and sharing it with others. This is a huge step, but it’s easy to stop there, reaching what could be called the “Git Plateau.” On this plateau, you have a functional workflow, but you’re only using a fraction of the tool’s power.

This basic workflow treats Git like a simple backup system. However, Git is a distributed version control system designed for much more than just saving files. It’s built to help you manage complexity, isolate changes, and maintain a clean, understandable project history.

This article introduces five powerful concepts, taken directly from Git’s core toolkit, that will help you move beyond the plateau. Mastering these will transform your workflow from simple saving to sophisticated code management, improving both your efficiency and the quality of your project’s history.

1. The Staging Area: Your Commit’s First Draft

The staging area is more than just a holding place for your changes before you commit them. The mental model shift is moving from “saving all my changes” to “composing a specific, narrative commit.” By deliberately choosing what goes into your next snapshot, you can craft a project history that is clean, atomic, and far more meaningful.

The following commands give you precise control over this composition process:

git add [file]: This command adds a file as it looks now to your next commit. This deliberate act is known as “staging.”git status: Use this to see a clear distinction between changes in your working directory that are not yet staged and the changes that you have staged for the next commit.git reset [file]: If you’ve staged a file by mistake or want to make further changes before including it, this command will unstage the file while retaining the changes in your working directory.

This separation is incredibly impactful. It allows you to have multiple, unrelated edits in your working directory but only commit a specific, related set of changes. For example, you can fix a bug and refactor a function in the same session, but stage and commit the bug fix separately from the refactoring. You can see this separation clearly by comparing the output of git diff (which shows all changes not yet staged) with git diff --staged (which shows changes that are staged but not yet committed).

2. Stash: The Ultimate ‘Save for Later’ Button

Imagine you’re in the middle of a new feature when you’re asked to fix an urgent bug on the main branch. You have a lot of modified files, but you’re not ready to commit them. This is where git stash becomes a lifesaver. It allows you to temporarily shelve your changes so you can get a clean working directory to switch contexts.

These commands form the core of the stash workflow, which operates on a “stash stack” (last-in, first-out):

git stash: “Save modified and staged changes” onto the top of your stash stack, reverting your working directory to match the last commit.git stash list: This will “list stack-order of stashed file changes,” showing you a history of your stashes.git stash pop: Applies the changes from the top of the stash stack to your working directory and removes them from the stack.

Stashing is a powerful feature for maintaining focus and handling interruptions gracefully. Instead of making a messy, incomplete commit like “WIP,” you can set your work aside cleanly, address the urgent task, and then return to your work exactly as you left it. If you want to apply the changes but keep them in your stash for later use, you can use git stash apply instead of pop.

3. Branching: Lightweight Isolation for Everything

A common misconception for those new to Git is that branches are reserved for large, long-running features. The reality is that Git branches are incredibly lightweight and are designed to isolate even the smallest changes, from a one-line bug fix to a major architectural change.

Creating and switching between branches is a fast and simple process that should become a regular part of your workflow:

git branch [branch-name]: Instantly “create a new branch at the current commit.”git checkout: “switch to another branch” and update your working directory to reflect its history.git merge [branch]: Once work is complete, this will “merge the specified branch’s history into the current one.”

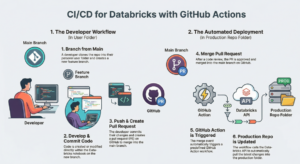

By creating a new branch for every distinct task, you ensure that your main branch always remains stable and deployable. This practice is the foundation of modern software development workflows like Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment (CI/CD), where a stable main branch is non-negotiable. It also makes your project’s history, as viewed through git log, a clear and understandable record of parallel lines of development.

4. History Rewriting: A Superpower to Use Wisely

Git’s history can feel permanent, but one of its most powerful features is the ability to rewrite that history—at least, your local version of it. This allows you to clean up your commits, combine related changes, and present a more polished history before sharing your work with others.

Two primary commands offer this capability:

git rebase [branch]: The technical definition is to “apply any commits of current branch ahead of specified one.” It works by taking each commit from your current branch, one by one, and “replaying” it on top of the target branch. The result is a much cleaner, linear history.git reset --hard [commit]: A more drastic command used to “clear staging area, rewrite working tree from specified commit,” effectively discarding any subsequent commits.

These tools are fantastic for tidying up your local commit history before you push it to a shared repository. However, they come with a critical warning: rewriting history is a destructive operation. You should use these commands with extreme caution on branches that have already been pushed and are being used by others, as it can create significant confusion and conflicts for your collaborators.

5. Becoming a History Detective

Beyond just viewing history with git log, Git provides powerful tools that allow you to inspect, compare, and analyze your project’s history to uncover valuable insights. These commands let you ask complex questions about your code and get definitive answers.

Become a history detective with these advanced inspection commands:

git log branchB..branchA: This shows “the commits on branchA that are not on branchB.” It’s perfect for seeing exactly what a feature branch adds.git log --follow [file]: This shows “the commits that changed file, even across renames,” giving you a complete biography of a piece of code.git diff branchB...branchA: This shows “the diff of what is in branchA that is not in branchB.” More precisely, it shows the changes onbranchAsince the two branches diverged from their common ancestor.

These commands are the engine behind the pull request views on platforms like GitHub. git log branchB..branchA generates the list of commits, and git diff branchB...branchA populates the “files changed” view. Mastering them allows you to track down when a bug was introduced or understand the full scope of a feature. For the ultimate detective work, your next step is to explore git bisect.

Conclusion: From Saving Files to Crafting History

Moving beyond add, commit, and push is the key to unlocking Git’s true potential. By embracing concepts like the staging area, stashing, frequent branching, and history inspection, you elevate Git from a simple backup system to an active partner in crafting high-quality code and maintaining a clean, collaborative development environment.

What’s one Git command you’ve discovered that has fundamentally changed your workflow?